Ports are dangerous enough workplaces without appalling conditions – including some truck drivers working 20 hours in a day – being forced on workers in the USA.

These dangerous practices also reinforce why the TWU’s campaign for Safe Rates is so important.

Being a truckie is Australia’s most dangerous job. For over 20 years TWU members have been fighting for safe, fair rates for truck drivers and safer roads for all Australians.

Safe Rates guarantees that every truck driver on our roads is behind the wheel of a well-maintained vehicle, won’t have to risk falling asleep on the job just to make a living and isn’t trying to meet an impossible deadline.

We stand in solidarity with these American truck drivers. Any Australian drivers being forced to work in an unfair or unsafe way should contact the TWU immediately.

Asleep at the wheel – from USA TODAY

(click link to view original article)

Every day, port trucking companies around Los Angeles put hundreds of impaired drivers on the road, pushing them to work with little or no sleep in violation of federal safety regulations, a USA TODAY Network investigation found.

They dispatch truckers for shifts that last up to 20 hours a day, six days a week, sometimes with tragic results.

In August 2013, a Container Intermodal Transport trucker, who said in depositions that he often broke fatigue laws, barreled into stopped traffic at 55 mph, killing a teenager and injuring seven others.

Seven months later, a Pacific 9 Transportation driver had just finished his 45th hour on the clock in three days when he ran over and killed a woman crossing the street.

A Gold Point Transportation truck was moving containers for 15 hours one day in May 2013 when it crashed in Long Beach, injuring four people.

But the USA TODAY Network investigation shows for the first time that fatigued truckers are a near-constant threat on the roads around America’s busiest ports.

To identify port trucking companies that put their drivers and the public at risk, reporters retraced the movement of thousands of Los Angeles-area trucks over four years using time stamps generated each time a driver passes through a port gate.

Reporters then calculated how long each truck had operated and compared the results to federal crash data from 2013 to 2016.

The analysis found that, on average, trucks serving the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach operated without the required break 470 times a day.

Those trucks were involved in at least 189 crashes within a day of an extended period on the clock. Federal records do not indicate who was at fault.

With some exceptions, federal rules say commercial truckers must take a 10-hour break every 14 hours.

The data alone don’t prove that a trucker was driving impaired. But regulators and experts said the analysis provides strong evidence of a problem they know to be pervasive but difficult to quantify.

“There’s enough there to warrant further investigation,” said Collin Mooney, executive director of the Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance, an association of industry regulators dedicated to improving safety.

As the USA TODAY Network first reported in June, California port truckers have been forced to work long days against their will.

Over the past decade, many companies pushed drivers into debt by requiring them to buy trucks through company-sponsored lease-to-own programs.

Drivers found themselves trapped in jobs that paid them pennies per hour after expenses. If they complained or refused to work past the legal limit, they could be fired and lose their truck along with thousands they paid toward its purchase.

Trucking company executives contacted by USA TODAY Network denied allowing their drivers to violate fatigue rules. Some noted that two drivers sometimes share one truck, a practice that could account for long stints of activity.

“We believe your analysis of driver gate data is perhaps a bit misplaced,” said Kevin Dukesherer, president of Progressive Transportation Services.

Dukesherer did not say how many of his trucks were driven by multiple drivers or address specific instances of overtime driving revealed in the data.

Drivers say sharing a truck is rare because many companies prohibit it. Far more common, they say, are truckers who feel compelled to work long hours.

More than once, he said, he found himself hallucinating, a side effect of extreme sleep deprivation.

“There are some days when you can’t think right anymore,” he said. “You can’t tell if you’re driving or not. You just have to continue working.”

Caught at the gate

Recognizing a potential public health threat, the federal government first began limiting commercial truckers’ driving hours in 1938, holding them to 60 hours a week.

Decades of study led to more stringent rules as researchers concluded sleep-deprived drivers become exponentially more hazardous the longer they spend on the road.

Regulations dictate how long drivers can be on duty each day, how long they can actually drive and how many hours they must take off in between.

Even so, the tools used to flag truckers who stay on the road too long haven’t changed much.

Police and Department of Transportation inspectors still rely heavily on paper logs maintained by the drivers themselves.

The first federal mandate to install electronic log machines in commercial trucks takes effect in late December, although questions remain about how quickly companies will comply.

In the absence of an accurate tracking system, the USA TODAY Network used publicly available records to build a database noting each time a truck entered or exited the ports of Long Beach or Los Angeles. The data offer a rough sketch of how thousands of trucks operated each day from 2013 through 2016.

It shows 580,000 instances where trucks spent at least 14 hours on the road without a 10-hour break. Those would be violations if a truck was operated by just one driver.

The activity amounts to about 8.3 percent of the total traffic from the ports, but represents a substantial amount of time on the road.

Assuming drivers picked up a new load each time they went in and out of a gate, those trucks moved 1.6 million shipping containers along Los Angeles-area highways over four years.

Reporters shared their results and methodology with researchers who have been studying commercial trucking safety for years at Michigan State University.

Professor Yemisi A. Bolumole said the analysis makes clear that safety laws have not been enforceable because “we are relying on carrier or driver honesty.”

At the request of the USA TODAY Network, Bolumole’s fellow researcher, Jason Miller, reviewed federal Department of Transportation data on safety and maintenance citations from a sample of large trucking companies across the country.

He found that port trucking is consistently one of the most dangerous sectors in the industry. Its drivers are almost 50 percent more likely to break hours-of-service rules than the industry average.

“It’s mind-boggling,” Miller said.

The office of Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti called for investigations into companies that create a public health threat.

“Federal hours of service laws exist for the safety of drivers and all of us,” press secretary Alexander Comisar said. “Violations are unacceptable and where they may have occurred they need to be promptly investigated.”

Law enforcement officials and experts say companies are legally responsible for knowing the hours their workers drive.

It can be a federal crime if managers routinely encourage or pressure truckers to stay on the road past the limit.

“Companies that force exhausted truck drivers to stay behind the wheel are gambling with the lives of everyone on the road,” California Sen. Dianne Feinstein said in a statement.

In the competitive, cut-throat world of container delivery, many companies are willing to risk using fatigued drivers, the USA TODAY Network found.

Gate entry data show that nearly 900 port trucking companies dispatched at least one truck past the legal limit over four years.

Some of the busiest companies each had thousands of potential violations.

Lincoln Transportation trucks operated 5,200 times for more than 14 hours without a 10-hour stop. That is about 6 percent of company activity from 2013 to 2016.

Since 2014, Lincoln drivers have repeatedly accused the company in ongoing lawsuits of cheating them of fair pay.

One Lincoln trucker, Jose Arroyos, testified in a 2016 California Labor Commissioner case that he worked almost 15 hours a day, five days a week, for three years.

Lincoln Transportation did not respond to multiple requests for comment. In labor court, executives denied pressuring drivers to work against their will.

Lincoln trucks have been involved in 29 crashes that injured six people from 2013 to 2016, federal records show.

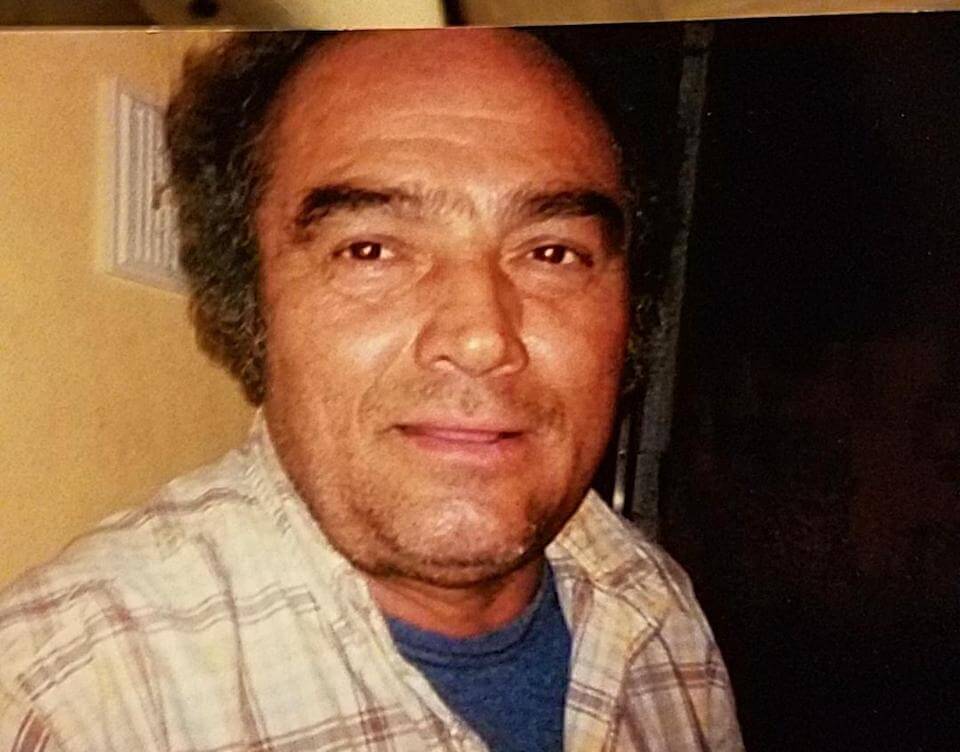

Freddy Uriarte, a father and grandfather, drove for Lincoln Transportation when he crashed and died in 2014. He had slept for a little more than four hours the night before the crash. Drivers say it is common for port truckers to work on little to no sleep while they deliver containers around Southern California.

Freddy Uriarte, a father and grandfather who drove for Lincoln for four years, died in one of the accidents.

Police reports, interviews with family members and port records give a clear picture of Uriarte’s breakneck schedule leading up to his death.

On a Wednesday in March 2014, he went to bed at 5:30 a.m. after 26 hours of hauling containers over two days.

Four and a half hours later, Uriarte was awake, running errands before his commute back to work.

By 1 p.m. he was moving containers again. He drove without a break until nearly midnight, when he was on his way to the city of Chino with a load of black Rosetti handbags and totes.

Uriarte didn’t notice what everyone else on Riverside Freeway saw — a broken down FedEx rig.

His truck slammed into the back of the trailer at full speed and collided with another car in the next lane.

Uriarte died in the hospital. The other motorist, Jeffrey Brunner, survived with a broken back and head injuries.

Since the crash, he’s had chronic back and neck pain. He said he’s struggled with constant feelings of loneliness, anxiety and persistent gaps in memory.

“It’s getting to the point where I can’t remember what I had for dinner last night,” Brunner said.

One of Uriarte’s sons, Carlos, once drove a truck at the harbor. He quit in 2008, when he found himself regularly working 8 am to 2 am.

“I left because I couldn’t take it anymore,” Carlos said.

Weak enforcement

Despite a groundswell of driver testimony about being pressured to work while dangerously fatigued, state and federal regulators have done little to curb the problem.

USA TODAY Network’s analysis of gate and inspection data shows that even when regulators check trucks that have been on duty 14 hours or more, they have cited them for breaking time rules less than 2 percent of the time.

Trucking law enforcement experts say that disparity shows the difficulty police have proving fatigue violations.

“There is a tremendous amount of hours violations that we do not catch,” said Mooney at the Safety Alliance.

Most of the busiest companies serving California’s ports received “satisfactory” safety ratings from the California Highway Patrol after their most recent inspection, state records show.

Reporters reviewed five years of state inspection reports from 10 companies with histories of labor complaints. Of the more than 300 violations inspectors uncovered, only one involved a driver’s hours on the road.

Pacific 9 illustrates how regulators fail to hold companies accountable, even when there is evidence of hours violations.

According to state records, the trucking company has not been cited for an hours violation in at least five years.

But 20 drivers have testified in recent labor court cases that they worked up to 19 hours a day and wouldn’t get paid until they falsified inspection reports. Pacific 9 has denied those allegations.

Gate data show that Pacific 9 drivers may have operated past the legal limit more than 8,000 times from 2013 to 2016. The company didn’t allow two drivers to share a truck, company executives said.

In January 2015 — the same month California Highway Patrol officers visited to inspect the company — trucks appeared to have been on the road without proper breaks at least 120 times, the data shows.

The officers’ visit that month was prompted by a tipster who alleged Pacific 9 had been dispatching drivers over the legal limit and then destroying the evidence.

But police couldn’t find proof and determined the allegations of excessive hours were unfounded.

Jon Wong Park is one of many Pacific 9 drivers who have talked openly about violating fatigue laws.

He said company dispatchers would tell him to change his logbooks if they showed hours that might get the company in trouble.

“Legally they’re supposed to stop me,” Park recalled in an interview with reporters. “But they kept giving me the jobs.”

By 11 p.m. on March 26, 2014, Park had worked more than 45 hours in less than three days, port data show.

As he pulled into desert city of Victorville, he didn’t see the woman crossing Hesperia Road in front of him until it was too late.

Jon Wong Park struck and killed pedestrian Bernice Williams in Victorville, Calif., on March 26, 2014. It was his 45th hour of work in three days. Park is one of many drivers who said his company, Pacific 9, often dispatched him past the legal limit of hours.

Bernice Williams went under the truck’s grill and died from head injuries.

The San Bernardino Sheriff’s deputy who first investigated never checked Park’s logbooks the night of the accident because “he has no official training in commercial enforcement,” according to the department.

Park said he didn’t fall asleep at the wheel that night and denied feeling overly tired. He was convicted of misdemeanor hit and run, but faced no other charges.

Pacific 9 Chief Operating Officer Alan Ta conceded the company’s drivers “had issues with hours” until recently, when Pacific 9 stopped using independent contractors.

Today all company drivers are employees, which makes them easier to monitor, he said.

“I don’t think it was just us,” Ta said of his drivers’ hours violations. “It was multiple companies.”

“That’s the past. I’m not trying to change the past. What’s done is done.”

About the data

To track drivers’ time on the road, the USA TODAY Network analyzed more than 30 million electronic time stamps generated each time a truck passed through the gate at the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles from 2013 to 2016.

Federal regulations generally require that a commercial trucker cease driving his truck no later than 14 hours after first coming on duty and not start again until he has had a 10-hour break.

We found about 580,000 potential time violations where a truck appeared to be operating for too long without a full 10-hour break.

The data have limitations. Gate entry systems track information about trucks, not drivers. So the data can’t account for cases where multiple drivers share a truck. It also can’t account for commuting time and other driving time at the beginning or end of the day.

To identify accidents involving trucks with potential violations, we matched truck identification numbers in the gate move data to federal crash data collected by the Department of Transportation. That data do not indicate who was at fault.